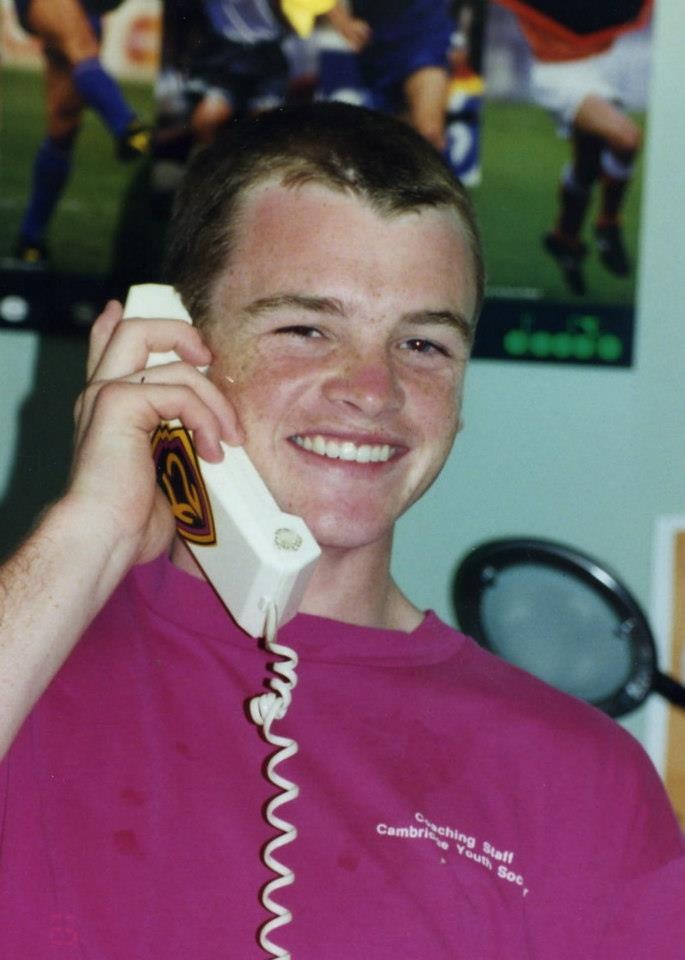

Casey’s son Eric (Courtesy of Casey Mulligan Walsh)

One day, early in August, the phone rings.

“Hello?”

“Eric Hendrickson, please.”

“Sorry, he’s not here,” I reply.

You have no idea how sorry I am he’s not here.

“We’re calling about a $60 check he wrote to Price Chopper on October 28. It was returned for insufficient funds.”

“Seriously? That was nine months ago.”

But God, it feels so good to hear someone say his name again. If only this were as simple as giving this wayward son of mine hell when he gets home.

“With fees, he now owes $82. If he doesn’t pay right away, it goes to our lawyer.”

I check in with myself, not sure just what I’m feeling. Apparently, I’ve taken too much time for the voice on the other end of the phone.

“Hello? Is he there?”

“No.”

“How can we get in touch with him?”

Ah, now I’ve put my finger on it. I’m actually looking forward to what comes next. Wearily glancing at the sympathy cards stacked beside the still unopened boxes of thank-you notes, I mutter into the mouthpiece, “He’s dead.”

“Dead?” I detect a note of skepticism.

“Dead. He died on June 12.”

Standing in the office, a sigh escapes me as I lean down and use my free hand to wrestle the filing cabinet drawers closed. They’re overflowing. Financial disclosure statements. Responses to family court petitions. Letters from the kids’ teachers attesting to my parental devotion. The divorce decree. It was 1999, and it had been a long three fear-filled years, culminating in one final crash, both figuratively and literally. My marriage was over, my 20-year-old son had died in a single-car accident, and my two younger kids were having an understandably tough time. There was, at last, nothing left to prove.

I’d surprised myself when Eric passed, possessing a calm I didn’t know was possible. They came, young and old. Together we cried, remembered him, and tried to make sense of something so utterly senseless. I reassured them all that whatever they wished they had said to him, done for him, he knew this now, and they could, like him, rest in peace.

But the legions of comforters had retreated to their own lives, and the house was terribly silent. Knowing that middle-of-the-night wakefulness would be my undoing, I stayed up into the wee hours, until I was exhausted enough to pass out on the bed. His bed, his things still taking up most of the territory, leaving just enough room for me to engulf myself in him, his smell, his presence slowly fading.

Eric’s death, so quickly old news. But the telling makes it real again — makes him real. They say his name and it brings him back, into the present, even if only for a moment.

“We’re sorry for your loss.” The disembodied voice jars me back to the issue at hand. “Just send us a copy of the death certificate.”

Oh, boy. It falls out of my mouth before I even have time to think.

“No.”

“No?” Her voice is incredulous. “Ma’am, we’ll need a copy of the death certificate.”

My words come out in a rush. “Sorry, I’m not sending you one. It’s public record. What’re you gonna do, have him arrested?”

“We’re attempting to collect a debt. Someone has to take care of this, or you’ll have to send us the death certificate.”

“I understand. I just won’t do it.” This is strangely exhilarating, freeing — refusing to explain, producing no evidence. I stop short of being rude, sticking instead to statements of fact. Several exchanges later, the collection lady wholly unsatisfied, I hang up.

That’s that, I think. But week after week, well into the fall, I answer the phone to hear the familiar request, spoken each time by a different voice, “Eric Hendrickson, please.” Each time, I tell them, “He’s not here,” and each time, a variation on the same drill.

“Would you like us to stop calling?”

“You bet,” I reply.

“Then send us a death certificate.”

“Nope. Talk to you soon!”

Another day, “We’re looking for Eric Hendrickson.”

“You’re gonna have a hard time reaching him,” I say, a little too gleefully.

Finally, I’ve had enough.

“Eric Hendrickson, please.”

“Listen,” I say. “He’s dead. He was dead the last time you called, he’s still dead, and he’s probably gonna be dead the next time you call. Why don’t you just save your money and stop calling?”

Weeks later, I realize they had. I couldn’t know we’d had our final skirmish until the phone had gone deafeningly silent.

I was sad when the calls ended; now there was no one saying his name. I’d won the battle, but in a strange way, it felt like I’d lost the war.

Casey Mulligan Walsh is a retired speech-language pathologist and writer who lives with her husband, Kevin, in West Sand Lake, New York. She is at work on a memoir.