Sterkte. In the Netherlands, that’s what we say to wish each other strength when something painful happens. We never wish each other softness or the ability to openly feel it all.

Toughening up is a virtue. Being rational is a virtue. Being in control shows strength. With such societal standards, it’s hard to create space for grief and loss.

My mom died from cancer when I was 20. Afterward, a friend sent me a card: ‘I wish we had better words in Dutch to say this, but we don’t. So I’ll say it in English: ‘I’m so sorry for your loss.’

I immediately realized she was on to something. In Dutch we really don’t have something similar. We use ‘my condolences’ (gecondoleerd, or met oprechte deelneming) as a catch-all for everything: from when we learn about a death to when we line up after the burial and offer our comfort to those grieving. It’s nice, sure, but it’s so formal. I wish we had something warmer. Something that feels like a hug.

As I quickly learned, it’s not only when paying our condolences that we don’t have the right words. There are so many holes in my native language when it comes to the experience of loss. Back in those early days, I didn’t know how to address how to fill those holes, and even if I did, I certainly didn’t have the energy to do so. But I did realize that language has power. Power to create a new reality. Power to make me feel less lonely when I could properly express what I was experiencing instead of using a catch-all phrase.

As a counselor, my role is to provide spiritual care to people. Philosophy, religious studies and psychology are my resources. Those fields have a lot to offer when it comes to exploring questions about meanings of life. From those resources I started researching words for things that hurt. I found that the ones that resonated most with me were the ones that had to do with bodily sensations. So I really started to pay attention to what was going on with my own body and realized it had a lot to say. And then I started a journal to keep a record of my experiences.

One of the odd things I noticed was that whenever I’d talk about my mom, I’d automatically switch back and forth between present and past tense. When I was talking to myself in my head, I’d use the present tense, because that felt most fitting to me. But when speaking out loud, wanting to be correct, and maybe even look normal, I’d speak in the past tense. Like there was a right way to grieve, and I wanted to be a good girl.

I wished I could have realized sooner what was going on. I wished I could have said: ‘My mom is in-between and so am I. I don’t want to talk about her in the past tense. This will happen in time, and I’m just not there yet.’ However, I did not have the perspective to look at it this way. I did not have the words for it. Now, I call this experience the ‘in between.

In my development as a human being this letting go of being a good girl was an important step. Instead of trying to live up to expectations, I started to do things my own way. ‘Expectations of whom?’ you might ask; and that’s the thing, I wasn’t even sure. Maybe it was society, maybe I integrated expectations of people around me or maybe they came from my own fears. It’s like thinking: ‘If only I could get things right, then nothing bad will happen to me’. This feeling of working hard and being in control is an important attitude in our society, as is the case in many western societies.

In the Netherlands we take pride in this attitude of working hard. ‘Being normal’ is a great good (it even was the slogan of the party of our minister president). ‘Don’t stand out’ is the norm. But very suddenly and very young, I learned that working hard and being normal won’t spare me. That’s not how things work in life. Things happen. Bad things happen. I better live my life my own way. I won’t be safe, I will get hurt and I certainly can’t protect myself by doing what I think is expected from me. That was exactly the lesson I needed to learn to make life worth living again.

This lesson helped me to publish the Dictionary of Grief. I wanted to create something that would help people tune into the wisdom of their bodies and take the time to describe those experiences, and take my own experiences as an example for what it could (not should) look like; to inspire and explore together. To let people know: you’re not alone, and you’re not crazy. This Dictionary led me to believe we need an experiential approach to grief. From there, we can develop a more accurate, experiential language. I’m still adding words because I’m still experiencing new facets of my loss.

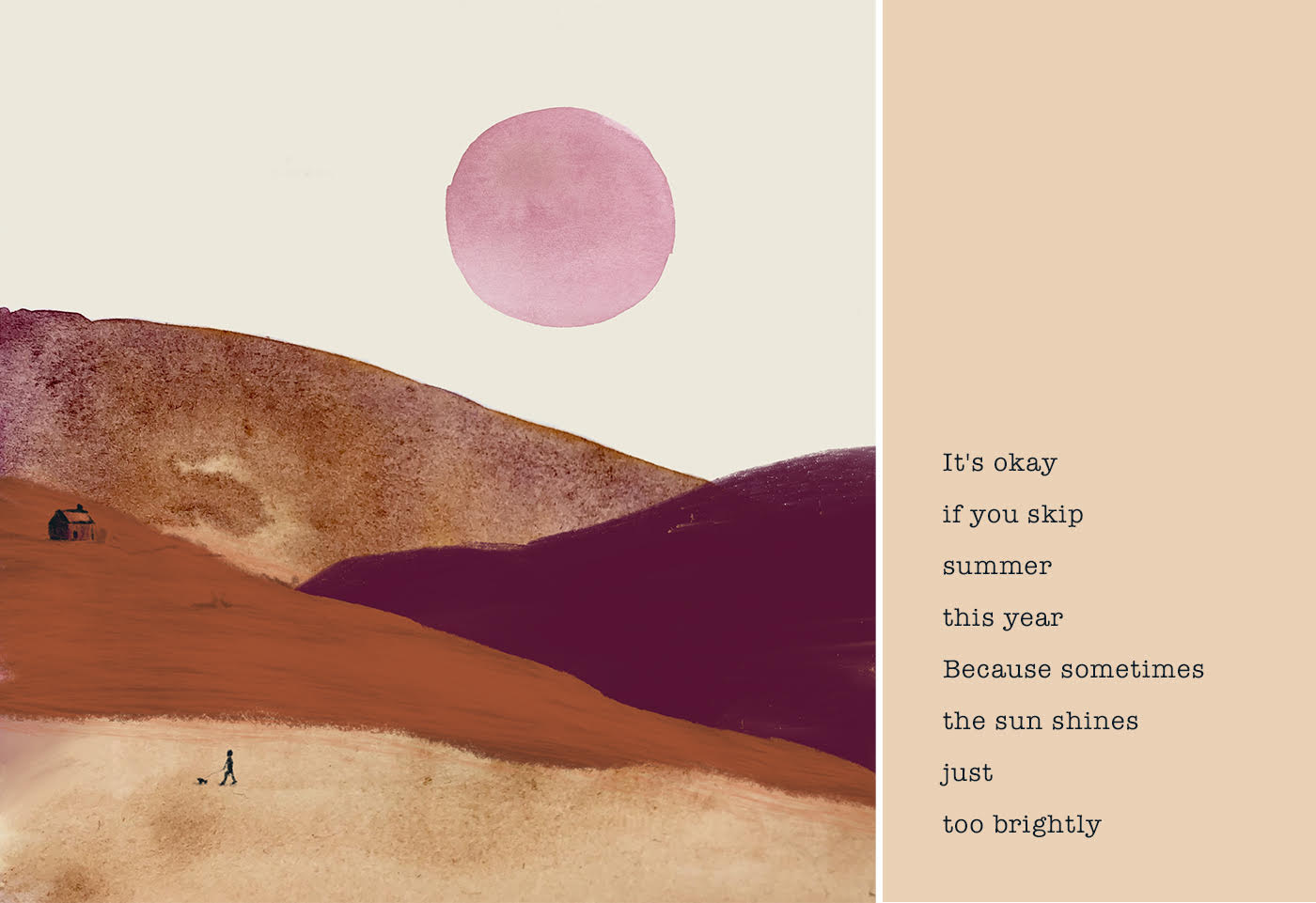

Another thing I did was to create ‘The Art of Loss’ (Verlieskunst) with Marlon Doomen, an illustrator friend of mine in Amsterdam. Together we create cards for all types of losses as an alternative to the more formal and cliché ones we have now which don’t offer a lot of choice or differentiation, like the ones I used to get after my mom died. That lack of cards is like a metaphor for the attention we have for loss. We don’t want to put too much emphasis on it. As though we are scared it will grow if we give it too much attention. The opposite is true in my experience. We need to hold space for each other’s pain.

Marlon and I create cards to send not only shortly after a loss, but also during anticipatory grief and across the long term. In this way, we can build a world that is able to bear witness and hold space for loss of any kind — because the world is full of it. We opened our online store this week and all the messages, orders, invites for events makes us feel like we are right on track. People are looking for depth and closeness, maybe even a little bit more in those challenging corona times.

We are pleased to offer a version of this essay in Dutch, available here.

Babet te Winkel lives in Utrecht, the Netherlands, where she studied at the University of Humanistic Studies. She is becoming a massage therapist specializing in grief and loss and is the cocreator of Verlieskunst.