Cultural tradition sweetens our celebrations, imbues our milestones with meaning, and connects our present to a rich and varied past. Ritual also helps us survive life’s hardest moment: Death. Franny Silverman curated stories of how people from a variety of cultural and religious traditions mourn and honor those who have passed, and includes a story of her own. The core shared value: Celebrate life.

Muslim Respect: Honor Your Parents, by Honoring Their Friends

Saifullah Johnson, African-American Muslim

I prayed in the company of rows of men I had never met before but who called me their brother.

My first time engaging Islam as a means of coping with grief was the Friday after my mother died. Three years and seven more funerals later, I was there again, this time to convert. I was 33 years old. What Islam gave me was a way out of no way. I converted the week Ramadan began and started fasting and attending the late night prayer services, Taraweeh, that month. I prayed in the company of rows of men I had never met before but who called me their brother. First Cleveland Mosque and other mosques in the area became my new home with my new family, from the U.S. and all over the world.

My major solace came from the du’a, or supplication. Du’a literally means “a soft calling out,” and one is encouraged to “make du’a” after Salat (prayer) and various other specific times. With sincerity that I’d never felt before, I was thanking God and asking God to help me with my problems — my grief, my depression, my loneliness, my money issues, my career, everything. My supplication was forcing me to take a hard look at myself and make some changes.

There are certain attributes a Muslim must have. A Muslim must be optimistic, patient, determined, kind, forgiving, and charitable. These qualities are all the pieces and parts that compose Iman, loosely translated as “faith in God.” A Muslim has to trust that God has a plan, that things happen for the good of a person, that the hardships of life are followed by ease. Hardships and tests are a part of every person’s experience, Muslim or not. Knowing that there will be an end to the hardship, either in this life or the next, helped me to sort through the suffering.

Creole Conversation: Talk About the Deceased

Madafi Pierre, Creole-American

When my grandmother died, my mother wore black for six months.

Talk. Talk about the deceased, talk to them, acknowledge that their spirits are here, and live with them even in the absence of their physical forms. My grandmother died nine years ago, and not a day goes by when someone doesn’t mention her. See, for my family, death is not really considered as the end. The spirit, which is so much more beautiful, never dies.

When she died, my mother wore black for six months. The Creole custom is that we wear black in moments of death but for just for a few weeks. The day of my grandmother’s funeral my mother announced to everyone that she would be wearing black for a very long time. Her best friend, her companion, her confidant, her critic, was no longer here and she wanted everyone and anyone to know.

My grandmother requested cremation, which is contrary to popular practice in the heavily Catholic and Seventh-day Adventist Caribbean community. This upset a lot of people in my family, but it’s clear that for all the cultural traditions surrounding death — being with the deceased as they pass, burial not cremation, having a wake at the home — the tradition that is strongest in my Mash-Up American family is strength of character and will.

Buddhist Inclusion: Bringing the Afterlife to the Present

Koca Wen, Jewish-Taiwanese-American

In China, Tomb Sweeping Day, or the QingMing Festival, is when you honor your relatives who have passed. You go to the graves and literally clean and dust the grave and lay out offerings such as fruit and crackers and burn incense. It is also customary to burn paper money, joss, so that your loved ones will have more money and fortune in the afterworld.

We are here in this physical world to give gifts so they can have a better life in the afterworld.

My dad, grandfather and mom all passed away when I was younger. I am Jewish, but I grew in a very superstitious Buddhist environment. I have observed “funny” traditions that my grandmother and aunts would practice to pay their respects. As a child, my family would go to these specialty shops that sold paper money, intricate paper mansions, and paper sports cars to burn. We had altars at home and my family would burn incense sticks every morning and night to respect the gods and goddesses. I’m not sure of the exact meaning of them all, but basically we are here in this physical world to pay respect and give gifts so they can have a more comfortable and fortuitous life in the afterworld. My grandmother one year spent a not small amount of money to have doves released in the name of my mom, which would add fortune to her afterlife.

Sarah Charukesnant, Buddhist-Thai-Chinese-American

We celebrate those in our lives who’ve passed by thinking of them often. We talk about them often, we laugh when we share their stories and we remember them. Oftentimes in my family, we talk about my grandmother and grandfather as though they were still alive. And we include them in our current lives, by lighting incense and praying or talking to our ancestors when something momentous happens. For instance, when my husband and I got engaged, and when my son was born, I lit one incense stick (one for ancestors, three for Buddha is the rule) and shared the news with my grandparents. During QingMing, if we are in Thailand, we go to their gravesite and clean and sweep the area. We then light incense, pray, and of course: take our annual family photo.

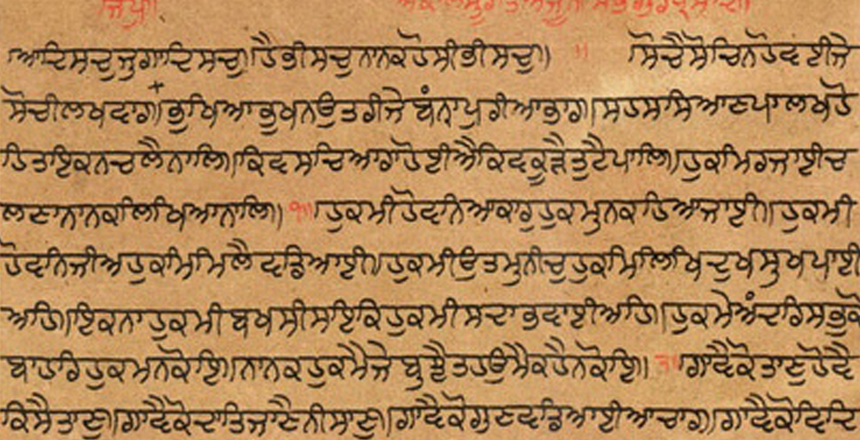

Sikhi Optimism: A Time to Celebrate

Related

Simran Jeet Singh, Sikh-American

Unlike many other religions, the Sikh tradition (Sikhi) gives no clear explanation on what happens to people when their lives end. Sikhi does not place emphasis on afterlife, and instead, encourages people to focus on what can be achieved within our present lives.

Celebrating rather than mourning pushes us to count our blessings.

The Sikh tradition teaches that life is to be lived with everlasting optimism (chardi kala). Therefore there is no ritual for mourning or grieving, even in a situation of a loved one’s passing. Sikhi views death as a part of life and the Divine Order (hukam). According to Sikh traditions, death is not a time for mourning, but instead a time for gathering, remembering, and celebrating. Because there is no clergy in the Sikh tradition, Sikhs comfort the dying and mourn their passing according to their wishes.

Many Sikhs prefer to listen to religious music (kirtan) and recitation (path) during their final moments, and many also choose to spend final time with their loved ones. A scriptural composition traditionally sung at the time of one’s passing is Sohila. The community has sung Sohila collectively since the formative moments of the Sikh tradition, and it continues to provide guidance and solace to those who reflect on its messages.

I find the Sikh tradition of framing death as an occasion for celebration to be incredibly comforting and powerful. This approach focuses on the positive contributions of one’s life and allows us to better preserve the memories and feelings of our loved ones. Celebrating rather than mourning also pushes us to count our blessings in a time of emotional vulnerability and helps us bring stability and solace into our lives, families, and communities.

Jewish Shiva: Together in Grief

Franny Silverman, Jewish-American

Jewish tradition says: There’s plenty of time to be alone with your grief. Right now, you need the comfort of others.

My uncle died on Christmas Day and the funeral was literally one day later. Family and friends came from as far as the Middle East with less than 24 hours notice. Traditionally, the mourners, the immediate family of the deceased, “sit shiva,” for seven days, taking breaks only for the Sabbath and holidays, though more and more people are sitting now for three days. The mourners traditionally sit on the floor or low stools, either rip a piece of their clothing or wear a symbolic torn black ribbon, do not shave, and are not allowed to cook or serve themselves. And because few look their best puffy-cheeked and red-eyed, all mirrors in the “shiva house” are covered.

Three times a day, the mourners are to be joined by a minyan, a total of at least ten people (traditionally men) age 13 or older to accompany them as they say the mourner’s prayer, the kaddish. This requirement of a minyan is about community support: even if you want to be alone in your grief, Jewish tradition says: There’s plenty of time to be alone with your grief. Right now, you need the comfort of others.

Cut to the first night of shiva after the Sabbath when my uncle passed. As his niece, I’m not considered immediate family, so I was among those serving and cleaning and prepping and organizing all the food and people who would come to sit with my mother and her siblings and parents, the mourners. We were short a few men for minyan. So I was tasked with calling neighbors who might be willing to come by for the brief service. My grandmother gave me a few names and numbers. I breezed through the list: yes, no, no, and then I called Herb Stein. A woman answered. Here’s how that went.

“Could I please speak with Herb?”

“Who?”

“Herb. Herb Stein…?”

“Wrong number.”

“Okay.”

I went back to my grandmother to report. Yes, no, no, and wrong number.

“Wrong number?! You must have dialed wrong.”

“Okay.”

I called back: “Hello! May I please speak with Herb Stein?”

Click. Dial tone.

I called back one more time. I was desperate. We needed a minyan so the kaddish could be said, so we could all go to sleep and start the shiva cycle over again tomorrow. Herb, please!!!

Ring…ring…ring…no answer.

I left a message: “Herb Stein…? Gladys and Norm’s granddaughter…shiva minyan for their son, my uncle…stat? Please?”

Not two minutes later, ring ring from an unknown number.

“Hello?”

“Is this Gladys and Norm’s granddaughter?”

“It is.”

“You called for Herb Stein?”

“I did!”

“Well, there is no Herb Stein at this residence. However, my husband is named IRV Stein.”

“IRV Stein! Yes, of course, Irv! I’m so sorry, Mrs. St—”

“You need one more for shiva minyan?”

“Yes.”

“He’ll be right over.”

“Thank you so much. And I’m so sorr—”

“Well, next time you should know who you’re calling.”

“Yes, of course.”

“Okay. Goodbye.”

“Goodbye. Thank —”

Click.

This piece was first published on The Mash-Up Americans, a site about all of our multifaceted (and hyphenated) identities. Learn more about Mash-Up, its mission and its founders here.