When the undergraduate creative writing class I teach gathered for our first meeting after the holiday break, one of my favorite students shyly approached my desk to tell me that she’d been given my memoir, “Invisible Sisters,” for Christmas. She is a strong writer who had expressed interest in writing about tough topics, so I jokingly asked, “Now that you’ve read it, are you still talking to me?”

Looking away, she mumbled, “I’m not sure.”

In that book, I’d written about learning to survive the deaths of my two beloved younger sisters to separate genetic illnesses. That meant writing plainly about my drug use and abortion in my twenties. Writing about the abortion worried me not because the topic is divisive, but because I was afraid it would be too much of a detour for the reader. But the abortion belonged in a narrative about my sisters and me, about children born and dying, and about love and survival. So there it was.

I know a writer who says that we can never tell what will offend a reader. We might think writing the lurking secret of a rape, a death or a robbery will be the culprit, but an uncle might surprise us by reacting badly to what we were sure was an innocuous retelling of a birthday party. This is why Amy Rogers Nazarov, who is working on a book addressing depression, adoption, and stereotypes about transracial parenting, tells me that “you might as well try to please yourself and tell the truest story you can.”

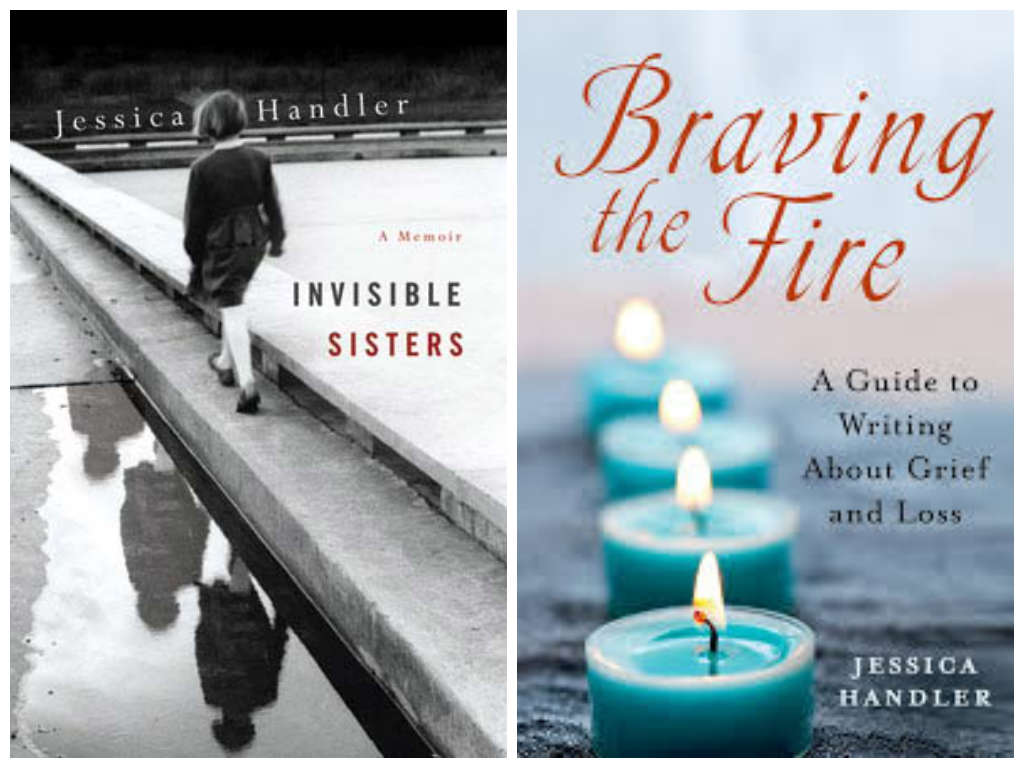

Since “Invisible Sisters,” I’ve written “Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Loss,” and teach workshops about writing well about loss. I meet authors almost every week who struggle with what might happen if they write about a potentially offensive topic. Here’s what I tell them:

1. Claim your right to your own memories. Emotional truth and provable truth are different. Provable truth is verifiable fact, like the date of a disaster. Emotional truth is the power a story element holds for you, such as how someone made you feel. Signal phrases such as “I remember” or “I believed” help identify a written scene as drawn from emotional truth, acknowledging that others might feel differently.

2. Cultural attitudes and laws may have changed over time. What you feared revealing when you were 15 might not have the same destructive power now that you’re grown. As an adult, I can write about my teenaged shoplifting. Back then, admitting my misdeeds would have gotten me into parental trouble and maybe even arrested. Today, there’s no impact on my adult life.

3. Vindication derails your narrative. Good writing needs conflict, not one-sided venting, so try writing about your anger from both sides. A story about divorce, for example, is also a story about marriage. Establish that conflict and the plot and characters will achieve more balance, which may be less likely to offend.

4. Who can sue? As a general rule, public figures and the deceased can’t prove libel under United States law, although there are some exceptions. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press has this libel primer. If you’re truly worried that you might cause a legal backlash, talk to an attorney. Many states have organizations offering pro bono consulting for the arts, and a meeting with an expert may be what you need to set your mind at ease

5. Write in service to the story. The abusive family member, the drug use, the suicide, the stuff that’s ugly in “polite company” are often what’s brought us to the desk. Tell your nagging “you can’t say that” voice that right now, you’re only writing for yourself. Once you’ve written that draft, ask yourself if it’s as damaging as you’d feared. What would make you comfortable with the material? You may find that you never use all of what you’ve written, but that writing has cleared the air, allowing you to write beyond what you feared would offend.

My student did speak to me again, and her initial discomfort led to a satisfying conversation about what we choose to reveal when we write about loss. I told her, finally, that there’s nothing in those pages that I wouldn’t tell a friend.

Jessica Handler is the author of Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief.” Her first book, “Invisible Sisters: A Memoir,” was named one of the “Twenty Five Books All Georgians Should Read” by the Georgia Center for the Book. Her nonfiction has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Drunken Boat, Brevity, Newsweek, The Washington Post and More.