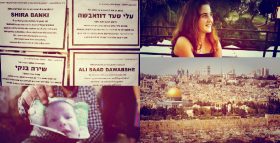

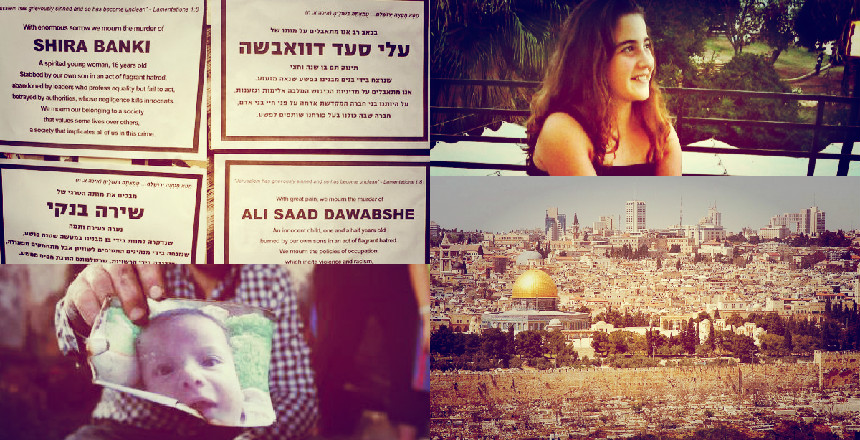

Clockwise from top left, the signs created by the author and a friend, Shira Banki, a view from Jerusalem, and a man holds a photo of Ali Saad Dawabshe.

In Israel — and especially in Jerusalem, where I am living — grief is a public affair. Call me morbid, but it’s one of my favorite things about this place.

Posted on walls and in shop windows, sometimes layered dozens deep, stark, black-on-white mourning notices announce recent deaths and, sometimes, where the family will be observing the traditional Jewish mourning period. Imported from the Eastern European broadside tradition, each of these posters is a little island of sadness in a sea of noise. They testify to what’s often said about the place: that despite its significance on the world map, Jerusalem remains a provincial town where the theory that everyone on the planet is separated from each other by, at most, six degrees, seems reduced to two degrees, max.

So amid the horrific murders in recent weeks of two children — one Palestinian, one Jewish — my friend Romy Achituv, an artist and native Jerusalemite, and I designed mourning notices in Hebrew and in English, the two languages most spoken by Jews here, for Ali Saad Dawabshe, just 18 months old, and Shira Banki, 16.

Related

The killings set off immediate waves of self-reflection throughout Israel and in Jewish communities across the world. The first death was baby Ali when, on July 31, in the West Bank village of Duma, the Dawabshe home was firebombed and the toddler was burned alive. Fanatical Israeli settlers are suspected in the attack, which would, one week later, also kill Ali’s 32-year-old father. (Ali’s mother and 4-year-old brother remain in critical condition in Israeli hospitals.) The second death was caused by an ultra-Orthodox man who stabbed six people, including Shira, at the Jerusalem Pride March a day earlier.

We were moved to create these mourning notices because we wanted the self-reflection the incidents sparked to continue even while people were living their lives around town. We wanted to encourage our fellow Jews and Israelis to feel these public tragedies as intimately as they would a death in their own families, and to consider how they — and all of us — are implicated in these hate crimes, whether through our own biases or by not speaking up about others’. Mid-way through the first day of taping up mourning notices for little Ali in downtown Jerusalem, we learned that Shira had died of her knife wounds. That night, we created a sign in her memory as well.

Despite our desire to spark a public dialogue, we undertook this project for ourselves as well. We were glad to put our grief and distress to work.

Not long after I put the photos on social media and sent word to a couple mailing lists, strangers started contacting me, both about wanting to join in, and to tell me that they’d been printing out the signs and putting them up in their own neighborhoods and cities as well. We also started hearing from others, and seeing for ourselves, that the notices in honor of the baby were being torn down at an alarming rate, both in Jerusalem and in Tel Aviv. Those for Shira, however, were by and large left intact.

There’s a political analysis to make here, about people’s willingness to condemn a policy that hurts people they see as similar to themselves more than those that ostensibly hurt only the other (and that argument is being made), but it’s also worth pointing out something underlying that observation: These notices are being torn down because being reminded of death in the public sphere is uncomfortable. Worse yet is being reminded of complicity.

From the beginning, we saw this project more as social engagement than as art, but the range of emotions it has sparked in people we spoke to and heard from, from rage to gratitude, certainly has something in common with art. If there’s one positive takeaway from this period of nightmarish violence, it’s that small, individual actions might actually make a difference in how people see the world. And that perhaps grief and even outrage have a role in healing the fissures.

Ilana Sichel is a writer and editor currently based in Israel. She tweets, occasionally, @ilanasichel.