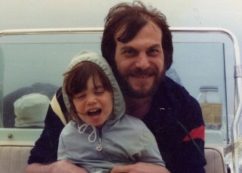

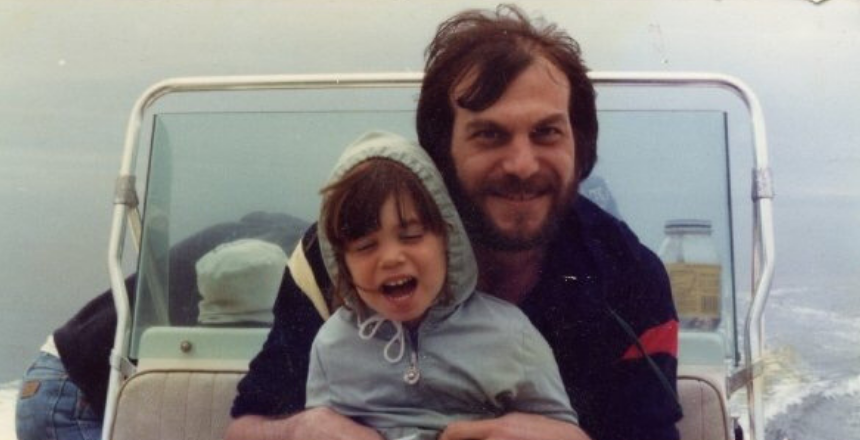

Jennifer and her father in Ocean City, NJ, 1982

Let’s just get this out of the way, straight off the bat. You can’t shield people from life.

When my father died, my Bubbe had already been in a Philadelphia nursing home for one hundred years. Don’t ask me how long it actually was because I was eight and time did not exist until July 15, 1983, when Melvin David Pastiloff died.

Those eight years I had with my father have to last a lifetime, so I have stretched them out and manipulated them as if they are my son’s Play Doh; little orange bits I find under the couch, pink hardened play-doh mixed with white stuck to the back of a remote, purple chunks in his toy kitchen set. The years with my father are like that too: they pop up when I least expect to find them, buried in between books and toy trucks and Paw Patrol characters. Memories. Whole years of my life that I thought had died.

My Bubbe had had a stroke and we’d cross the Ben Franklin bridge to go visit her on the weekends. Her cheeks sunk in towards her tongue as she’d ask how we thought her brisket had tasted the night before, even though she had been in the nursing home for one hundred years. I lie to myself that I remember those days but I really only remember my own poems that I have written about them.

I try not to lie to myself anymore. The only thing lying could protect me from would be myself. I will only have one cup of coffee. I will have one glass of wine. I will write things down so I don’t forget.

I wrote a poem in which I wondered if we should we lie to and say, “Your brisket last night was so good, Bub.”

Or, should we say, “Bub, there was no brisket last night. There will probably never be brisket again.”

I think my sister and I just kissed her fallen cheeks and felt afraid because it smelled bad in the nursing home and her confusion confused us. I clung to my Bernie doll (I wasn’t sure if he was Burt or Ernie from Sesame Street so I called him Bernie for both.) The stuff poems are made of. Bed pans and age spots and windows looking out into parking lots.

The 1980’s as one long poem.

My dad’s arteries had hardened. Technically, the way his life ended was awful and I wish I could unhear it as I do most things being a person with profound hearing loss. A few years back my mother informed me that he choked on his own vomit and suffocated.

My sister and I were not allowed to go to our Daddy’s funeral because people told my mother that it would be too much for us, that it would ruin us. She listened to their (bad?) advice and we have always felt a hole in the place of where the memory of his funeral should be. What color Play-doh would that be in my apartment? I will never know because it dos not exist. I fantasize about it even though it’s a creepy fantasy. Your father’s funeral? Weirdo. I don’t care. It brings me comfort to imagine mourners gushing about how funny he was. We loved him! He made the world go ‘round. We don’t want to walk the Earth if Mel isn’t on it!

Me too, people. Me too.

Meanwhile, my Bubbe sat in the nursing home waiting for her son to come visit, as he always did. She’d cry to my mom, “Why doesn’t my son love me anymore?”

My Bubbe sat in the nursing home waiting for her son to come visit, as he always did. She’d cry to my mom, “Why doesn’t my son love me anymore?”

Poems I have written about that time remind me that the reason no one wanted to tell her was because they believed it would kill her to know her beloved Mel had died.

What was killing her was thinking her son stopped caring.

My mom finally told her that he died. Was it better to know the truth? For the rest of my days, I stand by that yes. She died shortly after we relocated to California to start over.

The work I do now in my workshops is so much about bearing witness to each other’s human weirdness, and pain, and grief, and joy.

Some people die from heartbreak. I have also seen people who came close to dying but survived because of the other people who held them up, who bore witness to their grief.

They were the loving choices in the moment, both not telling my Bubbe that my dad had died and not allowing us to go to his funeral, both things aimed at protecting the hurting persons from hurting more.

But, do we get to do that? It may seem like protecting them in the moment, but it’s absolutely not in the long term. Same goes for lying to ourselves. We don’t need protection. We need hands to hold. And tissue boxes, and steering wheels to pound, and watches that belonged to our dead fathers which we think bring us luck, and people to watch breathing in their sleep, and books and funny texts and poems in old notebooks and friends who say I got you. That is protection enough because as far as the rest? We can never control loss.

We don’t need protection. We need hands to hold…That is protection enough because as far as the rest? We can never control loss.

We can only look into the eyes of whoever is left standing next to us and say. this is the way through. The lie might be that we actually know the way through, but that doesn’t matter because when we have that I got you person, we can wade our way through the waters of grief, or Play-doh, and we won’t be alone as we navigate the hard stuff.

I think my Bubbe died of a broken heart, but at least she knew the truth. It wasn’t that her son didn’t love her anymore. He was just dead. Perhaps it sounds sterile and cold, but once we can stomach the truth we can begin to heal even if it means we have a moment (or five hours) of grief every single day for the rest of our lives. There is no protection against life. She died knowing he loved her but he was gone.

Unfortunately, I don’t have a neatly organized summary about how we should always tell the truth and let people make their own decisions. My son is almost three and I have no idea the things I will do to try and protect him from the unfairness and pain of the world. I can lie to myself (and to you, dear reader) and say that I will never tell a lie, I will never look away, I will always bear witness. But I won’t.

Can we unhear things? No. Can we protect people from suffering? No.

But I can say this: I will do my best to be in my body when I feel things even though all I want to usually do is escape. I will do my best to walk shoulder to shoulder with anyone whose world had exploded, with anyone who thinks they couldn’t possibly bear the burden of truth. I will be their I got you person, even if it’s just during a funeral or the emptying of a bed pan or the picking up of Play-Doh. That’s all I can do.

Jennifer Pastiloff, founder of the online magazine The Manifest-Station, travels the world with her unique workshop On Being Human, a hybrid of yoga-related movement, writing, sharing aloud, letting the snot fly, and the occasional dance party. Find her at JenniferPastiloff.com and on instagram at @jenpastiloff. Her memoir, On Being Human (Dutton Books), is available now.