This year, on the second night of Passover, I left the seder in haste. I rushed home, grabbed my ID and health insurance card, then stuffed toilet paper in my underwear to soak up the blood that had started to flow out of me.

13 weeks pregnant and bleeding, I wrote on the sign-in sheet at the Emergency Room. My husband and I sat on the sticky, peeling leather chairs in the waiting room, and I clenched and clenched, trying to keep the blood inside.

The Hebrew word for Egypt is mitzrayim. Embedded in this word is another Hebrew word: tzar, which means, narrowness, or constriction. On Passover we tell stories of liberation, of a movement from mitzrayim — the place of constriction, the narrow place — to freedom. To a place of expansiveness.

As I lay on a hospital bed, loosely fitted into a blue and white hospital gown, a nurse drew vial after vial of blood from my arm and I tried to constrict the flow of blood that dripped through my cervix and out of me. I tried to squeeze my vagina shut.

Hour after hour passed. At 2 a.m., we were led along an empty, dark hallway surrounded by empty desks and empty rooms. A hospital after hours. We walked into a small room where, waiting for us, we found an ultrasound machine and an ultrasound technician. There I lay on another bed, hiked up my hospital gown, and watched the monitor. The ultrasound gel was warm on my stomach; cold sweat pooled under my arms.

A little head, I could see. Little ears. My husband started to smile. For a moment we forgot that it was the middle of the night and we were in the ER. We forgot that I was bleeding. We only felt that sweet, familiar thrill: a baby, there’s a baby inside me. Like the moment on a hike several weeks earlier when I, short of breath, stopped to stare out over the San Francisco Bay. Feeling my heart beating, I smiled, and said to my husband, “There are two hearts inside of me.”

But when I lay on the hospital bed in the dimly lit room, I saw the white dot in the center of the of the screen, in the center of the little figure. It was the same white dot that, at 7 weeks and 3 days, had been pulsing quickly, and obviously, at our first ultrasound. Now, the white dot was still.

The ultrasound tech took image after image. I saw him drawing green vertical and horizontal lines, measuring the figure on the screen. He turned the sound up and I heard a steady thump-thump-thump. “That’s your heartbeat,” he said, “or rather, the sound of blood in your ovaries.” Then he turned the sound up again and all I heard was white noise. A steady wind rustling, a river flowing. My husband stopped smiling. I turned my head to the side.

READ: Mizuko Kuyo: Japan’s Powerful Pregnancy Loss Ritual

The ultrasound tech walked us back through the same empty, dark hallway. He was quiet, too quiet. So I said, just to say something, “The baby is there, right?”

“Yes,” he said, “But I don’t see a heartbeat. And it only measures 9 weeks.”

Suddenly, in the blank hallways of Alta Bates hospital in Berkeley, California, at around 2:30 a.m. on the second night of Passover, I found myself face to face with the fear that had plagued me for much of my first trimester. The great what if.

Once, many years ago, I went on a silent meditation retreat. A woman asked, “What do I do about the pain in my shoulder when I meditate?” The teacher replied, “Sometimes, the resistance to the pain is more painful than the pain itself.”

My fear of miscarriage was not so different from that woman’s resistance to the pain in her shoulder. The pain of my constriction, of my fear that this might be, was indeed much worse than the pain I felt — and feel — now that it is.

And so, when the ultrasound tech said, “I don’t see a heartbeat,” I let go of my clenching. I stopped squeezing myself shut, stopped trying to stop the blood from flowing out. I released, and in so doing, found that I had arrived at a place of expansiveness. It was a movement from slavery to freedom, from narrowness to spaciousness.

READ: Everything I Didn’t Want to Know About Miscarriages, But Experienced First-Hand

Freedom, as I am learning, is not the absence of pain, but the ability to fully feel the pain of what is. I am no longer afraid of this sadness, this sorrow, this loss.

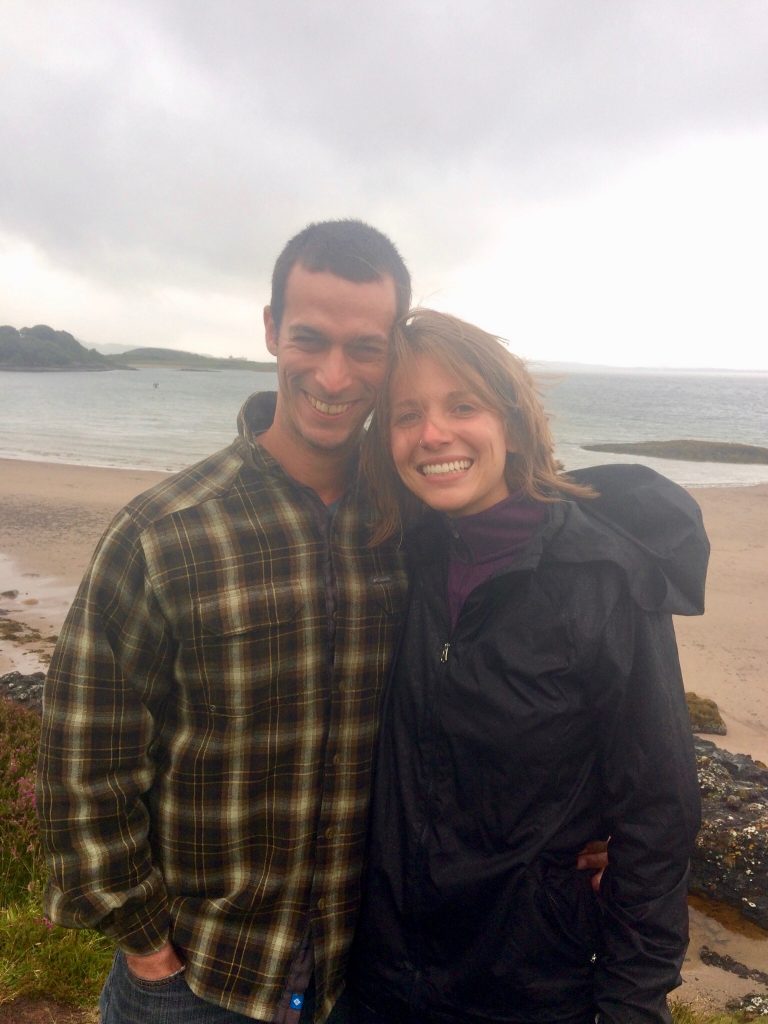

Noa and her husband Jack (Courtesy of Noa Silver)

This year, the Passover story happened in my body. The blood that rushed like a river out of me; the death of my first — though, I remind myself, it was not my first-born, but rather, my first idea, my first possibility. The death of my first pregnancy.

When I think about what I have lost — what my husband and I have lost — it is not the little embryo that was growing inside me that I think of first. It is, rather, the loss of a story. The loss of the narrative that we had been creating for ourselves. It is a loss of knowing, of control over time, of a sense of certainty that this will happen, and when, and how.

We are now, with each day, writing a new story. A story that incorporates this miscarriage into its pages, into its arc. For me, it is a story, strangely, of liberation.

And like liberation itself, it is a story that is bound up in others.

But now we had to make the calls. So many calls. And I thought that I couldn’t bear it. I was angry that we had told, upset that I now had to “un-tell.” I started fumbling with the syntax in my head. How should I say it? “I’m having a miscarriage,” “I’m miscarrying,” “The baby is miscarrying,” “It was a miscarriage,” “The fetus was not viable.” Language could turn this experience inside out. It could turn it into something clinical, or something personal; something to be ashamed of, or something to marvel at. What I wanted to say was, “I trust that my body is wiser than I am.”

Through the course of a day, my husband and I took turns on the phone. First my parents, and then his. Each of my sisters, and then all of his siblings. One friend at a time. And what we discovered was that each new telling, each act of storying, was its own catharsis, its own type of redemption. Each conversation ushered forth new tears, unleashed another layer of sorrow, and of loss, and of that bittersweet, now-familiar sadness.

With each call also came new stories. Stories about the women in my life, and in my extended community’s life. “My mother had a miscarriage,” said one friend; “My sister and sister-in-law,” said another. “My wife had two,” said a teacher; “my cousin,” said another. “Both your aunts,” said my mother. “I had a miscarriage,” said my husband’s grandmother, “and then went on to have four children. So take heart,” she said to us, “Take heart.”

In the days of bleeding and crying since the seder night, since that night we left in haste, I have started to believe that the process of miscarriage is much like the process of mourning, which is much like the process of becoming free. After the Israelites crossed the Red Sea, they wandered in the wilderness for forty years before arriving at the Promised Land. Freedom does not come in an instant. And neither, it turns out, does miscarriage. It took some time for my body to expel what it needed to expel.

Mourning, too, has not ended overnight. But I have found that the flow of tears is a little like the flow of blood. Both have ferried me somewhere new, to an altered state of being. And, just as the midwives told me would be true with the flow of blood, there were days when the tears were heavier, and more painful. Gradually, they have lightened, and perhaps soon, they will stop altogether. Eventually, I will not have to expel anything else; I will be able to hold whatever is left inside of me.

Noa Silver is a writer and adventurer. She and her husband recently returned from a 14-month journey that took them from caring for newborn kittens and cooking their meals over a wood-burning stove in Patagonia, to following a drunken guide over the snowy peaks of the Himalayas, to squeezing in between sacks of potatoes and baskets of cabbage on a 36-hour train journey that stretched across Myanmar. She lives in Berkeley, California.