Recently, a New York Times article about New Mom Friends went viral among my friends. It’s about how important it is to avoid isolation during our first few months as parents. We all need someone to text while we’re awake at 2 a.m., feeding the baby, or to stress with about our babies’ weight gain and sleep patterns.

I dutifully forwarded the article to all my pregnant friends, and then thought about how I’ve found a similar kind of kinship with my friends — and even acquaintances — who have also lost a parent. I’m in my mid-30s, so, for now, this group is fairly small, but fairly mighty, too.

I’m on board with the idea that it’s better to say the wrong thing than to say nothing, but my friends with dead parents — they are much more likely than others to say the right thing.

After I would share the latest grim hospital update with one friend, she would write something like “ugh that sucks, im sorry,” which was perfect. These friends never called me “strong,” or declared that my mom’s death was “God’s plan.” Yes, she had been doing pretty well (for someone with blood cancer), before sudden complications from a biopsy led to her death. But please don’t tell me that “at least she didn’t suffer.” I’m grateful for my friends with dead parents for knowing better.

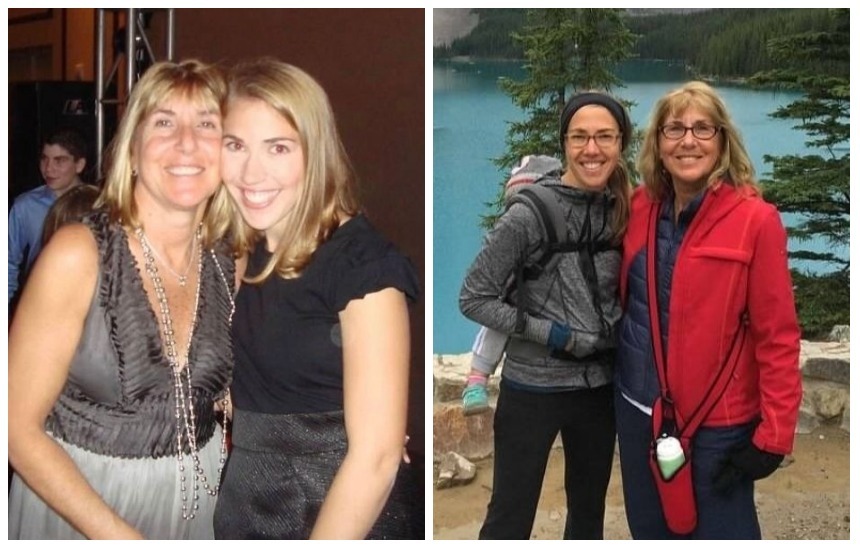

The author and her mom (Courtesy of Andrea I. Stagg)

These friends understand how it feels to leave a hospital each week, not knowing if our parent would be there when we returned. A friend who lost her dad a decade ago told me how her father discouraged her from taking a semester off from college or transferring schools to be closer to him. She understood the pressure I felt to spend sufficient time with my mom. (Is there such a thing as “enough time”?) She was validating and affirming at a time when I was unsure of every choice. Should I go for a run or take an early train to the hospital? Should I forego weekend time with my daughter or schlep her along, which would surely shorten our visit? Is a preschooler exactly what my mom needs today or would we be a nuisance to someone who needed rest?

After my mom died, I engaged in the Jewish tradition of sitting shiva for 7 days. My dad, sister, uncle, aunt, and I sat on uncomfortably low chairs as visitors poured in over the week, filling our days with conversation and stories, and jamming our refrigerator with deli platters. Family members sprang into logistical action, making sure there was always hot coffee and taking care of waste management. (There’s a lot of garbage at a shiva.)

Meanwhile, my friends who had sat shiva for a parent checked in often that week, assuring me that I wasn’t getting sick; I was simply dehydrated from the salty food and all the talking. They told me I didn’t have to entertain anyone, and if I needed to go upstairs or for a walk, I should. I was grateful for their insights and permissions.

My friends with dead parents don’t judge me. I can text them about reading my mom’s old emails. I recently confessed to one that I stood in my parents’ walk-in closet with my face buried into her clothes, deeply inhaling and then exhaling with sobs. These friends didn’t offer judgment or pity — just understanding, commiseration and love.

Best of all, having these experienced folks in our lives brings great hope because they are in a future phase of grief that seems more manageable (even though I know they all have moments of great sadness, no matter how long it’s been). I know that if they can start a new job, get married, have children, buy a new house and engage in everyday activities without their parent, I will be able to take on new challenges, too. Their successes assure me that while I’ll always love and miss my mother, it won’t always feel this bad.

Unfortunately, I’m already paying it forward, welcoming others into the unenviable club. So your daughter is growing out of the dress your late father bought for her? That sucks. I get it, and I’m sorry. I’m ready to be your new Dead Mom (or Dad) Friend, with no judgment or pity in sight.

Andrea I. Stagg is a lawyer, mom, runner, and library enthusiast living in New York City. She has Google docs about her Google docs.