By my 20th birthday, both of my parents had died.

It was all pretty terrible: losing, over the course of three years, the two people in my life who made me, loved and protected me; having to enter into an unlit tunnel of complex double bereavement that made me continually question which parts of my chaotic inner life were just me becoming an adult and which parts were the cruel work of the grief; the strange survivors’ guilt of seeing my family crumble from four people to two.

If you’ve been through something similar, you probably know what I’m talking about. At 20, though, I was mostly surrounded by not-quite adults who’d only just finished being teenagers, who’d not yet known traumatic loss. I had to navigate this with peers who couldn’t quite grasp why my voice sometimes sounded far away, bouncing off invisible walls. That was lonely.

Fast-forward 15 years, and I’m in a completely different situation. First, I’ve been able to gain some perspective on how grief works, how it affected me and how to manage my emotions around its consequences. The other thing is that many more people my age have by now experienced grief, are experiencing grief, or at least understand that grief might be around the corner for them. So, of course, they ask me for advice. And it’s is a very delicate thing to give that advice.

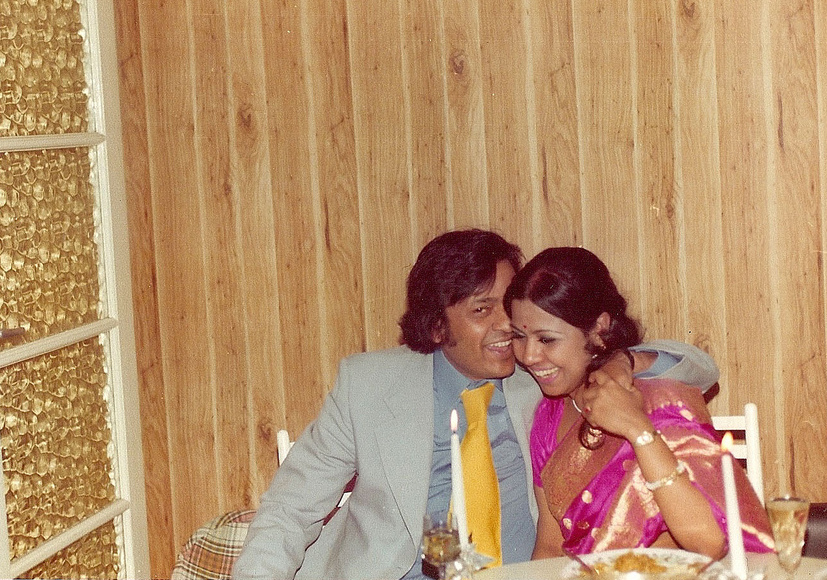

The author’s late parents. (Courtesy of Suchandrika Chakrabarti)

Because while there are some universalities to grief, it’s a state of mind and heart that’s all about the personal details, the specific relationship between the dead person and the living one who feels left behind, the silent inner battle over which tense to use at any given moment.

So no one person can be a definitive expert on everyone else’s grief. But for those of us who have experienced it and processed it, we may feel a responsibility toward those who are new to it. We see them standing at the mouth of a tunnel, unable to imagine the future stretching out on the other side, and we don’t want them to feel as lonely as we once did.

Here are my five suggestions on how to handle the new grief that another person brings to you because they don’t know what else to do with it.

- Now is not the time to talk about how it gets better.

Here’s the thing, she doesn’t actually want your advice, not this early on, no. She is just afraid of being alone with these awful new sensations, and the odd sense of having become a stranger to herself. Remember raw grief? You wanted to wallow inside it, make time stop and keep the departed person close. Looking to the future is terrifying. Don’t force that future on her right now.

- Remember that grief is the enemy of concentration.

Oh, the mind fog so common during the first year(s) of grief. Keep it simple, stay in the present moment. Ask: How are you feeling right … now? Remind them: You can say how shit it all is. Or if you want to sit here in silence, that’s cool, too.

- Acknowledge the unique nature of their relationship.

Mapping your more mature loss over his — even when it sounds like that’s what he wants from you — may not be particularly helpful at this time. Remember to ask about the person who’s died, and create a space for him/her to be spoken of. Say the name that people are now afraid to say because it might remind the mourner of their person (as if they weren’t thinking about them anyway), or it might remind others that they and their loved ones are also mortal (though there’s no denying that). What a comfort it can be to hear that name spoken freely, even though you both know the person who’s gone will never answer to it again.

- Normalize the idea of seeking communal and professional support.

There’s still so much resistance to acknowledging vulnerability and accessing help. There’s also a sense of worthlessness that tags along with grief; the feeling that only the person who’s died deserves compassion. The person who’s missing them, though, is told to just stay strong and carry on. There’s a knotted thread of grief-thinking that is oddly self-defeating in this way. Sometimes the best thing you can do is point people to the communal and professional supports that you, yourself, can’t provide.

- Know when you can’t do it anymore and remove yourself from the conversation.

Being seen as an expert in grief by others means that you will be called upon by very needy people you don’t want to turn down. That’s some very taxing emotional labor, and it will take a toll on you.

Keep these conversations within the boundaries of what you can handle, and learn how to extricate yourself from them in kind ways. You might do that with a hug, or with the honest admission that you can’t talk about this subject any further, right now. Delivering a truth like that to the newly bereaved is a gift because no one else is speaking clearly to them right now. After all, you have to be able to put your own headlamp on properly first, before helping someone else who’s just found the awful entrance to the tunnel.

Suchandrika Chakrabarti is a freelance journalist based in London. She makes Freelance Pod, and she’s on Twitter @SuchandrikaC.

Modern Loss is not a therapeutic adviser; this piece should only be used as a guide. Users should verify the veracity and appropriateness of the information posted on the site with his or her own therapeutic adviser.